SegWit is one of the most discussed topics in the history of Bitcoin and rightfully so. The solution to a multitude of Bitcoin’s problems was surprisingly effective. The activation, on the other hand, was a rollercoaster. Additionally, it is a very complex topic that requires you to spend a significant amount of time with it in order to get a complete understanding of its mechanics and implications.

One of the several issues that were solved by SegWit is the quadratic sighash problem. This seems to have been missed quite frequently by mainstream and even Bitcoin-specific media since reporting on SegWit’s reasoning seemed to focus mostly on its fix of malleability and the expansion of available block space. Since there are not many resources going into detail on this topic, I try to lay it out here and might follow up with other articles on other frequently missed aspects of SegWit.

The quadratic sighash problem

Let’s start by locating the problem: the quadratic sighash problem arises while hashing the transaction data. We need the hash of the transaction data to create a signature that can verify that an output is spendable by the person who created the transaction, i.e. the person who has control over the private key. The unspent outputs we are spending in a new transaction become inputs within that new transaction and each of them needs to be signed to prove that each old utxo is actually spendable.

The impact of this is not very dramatic when creating a transaction since there is only one person (the creator of the transaction) doing it only once. But Bitcoin’s security promise stems from the fact that any participant in the network can verify that all transactions in the history of the blockchain are correct. In fact, every full node must verify any transaction that ends up in a block that has been mined. So the impact of high computational complexity is much more serious in the validation of transactions than in their creation.

As the name implies, there is something quadratic going on while verifying a transaction. Quadratic complexity in an algorithm is certainly not something anyone wants to see in performance-critical code.

This matters to the Bitcoin network in particular because we want to allow as many people as possible to participate in the network, even if (and maybe especially if) they can not afford much computational power. Ignoring this could theoretically be exploited by miners who could have the interest to reduce the number of full nodes in the network by slowing them down to a degree that they can not stay up-to-date with the current tip of the blockchain, preventing them from being a participant in the consensus process. It is currently possible to run a full node on an older generation Raspberry Pi for example but this could be jeopardized by such an attack. This does not require hash power of anywhere near 51% of the network, a miner would only need to mine a malicious block with a high enough frequency that low-powered nodes can not catch up. An increased block size, as was in a heated debate in 2017, would increase the chance of it happening as it would leave more space for malicious transactions in a single block.

While the issue had already been reported in 2013, it became most apparent when f2pool mined a block containing a single transaction, which was taking up the whole block space of 1MB. Rusty Russell wrote a blog post on it the following day, naming it the mega transaction. This was not a malicious transaction but rather sweeping small spam outputs from weak ‘brain wallets’*, as you can observe in a block explorer.

The more significant part of this story is the time it took to validate this transaction: a Reddit poster reported that it took 25 seconds to validate. The poster did not provide hardware specs but we can assume that blocks usually will take less than a second to validate on up-to-date hardware. This was clear evidence that the quadratic sighash problem was not just a theoretical issue. A poster on Bitcointalk also noted in his post that a malicious transaction could be designed to do even more damage, estimating a worst-case transaction verification time of over 3 minutes on comparable hardware.

Let’s look at what is actually causing the quadratic time increase

in the signature hashing algorithm before SegWit.

We are talking about the computational complexity of O(n2),

or O(n) * O(n), where n is the number

of inputs in the transaction. So what is the first n and

what is the second n?

For each input in the transaction, we have to go through the following steps as described in Rusty’s post (and that

means here we also have our first n):

- We have to strip the other input scripts from the transaction. Note that the rest of the input data (TxId of the previous output and its index) remains.

- Replace the input script with the script of the output we are trying to spend.

- We double-SHA256 hash the resulting transaction construct.

- We check that the signature correctly signed the hash result.

The second n is admittedly not so easy to spot: As there still remains data within

the serialized transaction pre-image for every input, the size of data that needs to be

hashed still grows proportionally to the number of inputs. As mentioned before,

this data is the TxId of the previous output and the index of the output we want

to spend. This is our second n.

To make this more concrete, let’s consider a transaction with the minimal

number of inputs that make this issue occur: exactly 2 inputs. We loop over

both of these inputs and for each of them,

we need to hash both the previous output script of the input we are currently looking at

and the TxId and the index of the other output. These are two different sets of data. This

means we have performed 2 * 2 = 4 hashing operations.

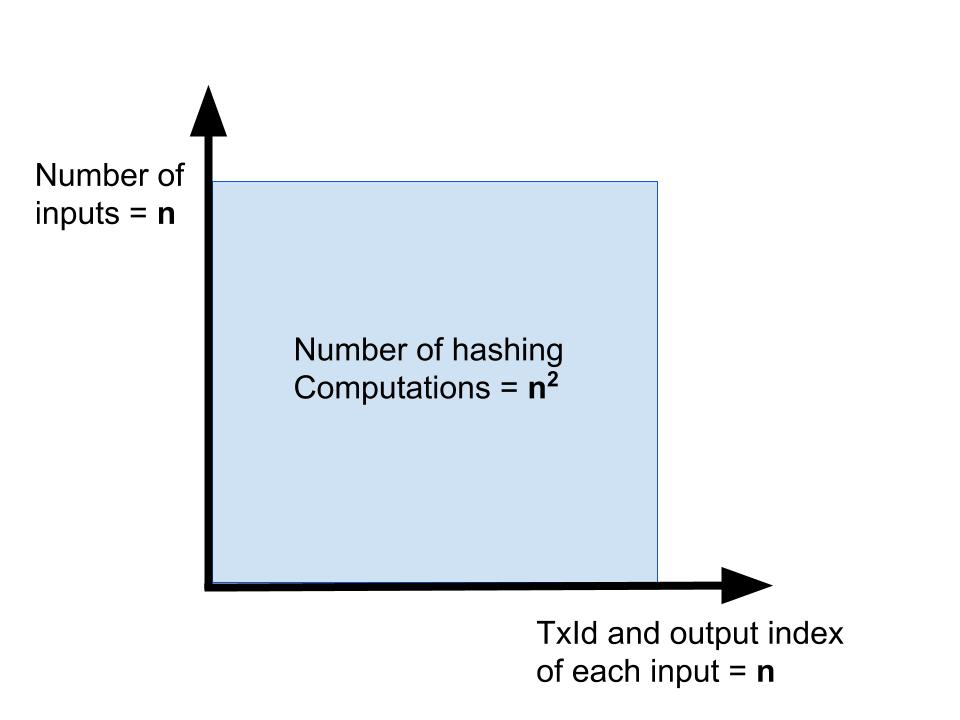

See also the following graphic where

I try to make this a little more visually intuitive if you are not thinking

about computational complexity on a regular basis.

(If you are not familiar with computational complexity and Big O notation I

recommend reading up on the subject in general if you are interested in

getting a deeper understanding.)

Also, see this graphic for a much more detailed view of the serialization process.

It also should be noted that the transaction needs to be signed with the SIGHASH_ALL flag, so all the signatures are actually checked.

How SegWit solves the problem

The breakthrough of SegWit lies in the name: SegWit stands for segregated witness and, if that sounds strange to you, I should add that witness stands for a proof that a statement is true in the field of cryptography. In the case of Bitcoin transactions, the statement is that whoever wants to spend an input is the rightful owner, i.e. has power over the private key. The proof is the signature that is attached to the input. In other words, SegWit stands for the separation of the input signature. As you have read above, the cause for the quadratic sighash problem is, in fact, that the data we need to hash for every input grows linearly with the number of inputs.

In SegWit transactions, the script signatures of all the inputs are not included in the serialization format that we need for the transaction hash. Instead, this data is moved to the end of the transaction. So, we do not need to repeatedly hash the transaction with all the different witnesses. We only need to hash the transaction once for every input in order to sign it. This means that the number of operations for each input now only grows linearly as step 1 of the 4-step process described above simply does not exist. This reduces the computational complexity of signature verification to O(n).

See the detailed overview of the serialized data in the BIP143 specification.

Other proposed solutions

For the sake of completeness, I want to mention that there were other proposals to deal with this issue. Most prominently the suggestion to limit the transaction size to minimize the damage that could be done by larger transactions. Particularly Gavin Andreesen suggested a transaction size limit of 100,000 bytes. The proposal was, however, dismissed by large parts of the community as it did not solve the root cause of the issue and thus, also left Bitcoin vulnerable to exploitations of the problem.

Conclusion

It is still fascinating to me how SegWit solved so many problems at the same time. While malleability was probably the main motivation for it, the quadratic sighash problem was a vulnerability that had been known for a long time and would not have been difficult to exploit, given a significant amount of mining power.

Removing the witness data from the transaction solved the root cause of the issue, lowering the complexity of the algorithm from O(n2) to O(n), making it an absolute non-issue, even in the event of future block increases.

Further reading

- BIP143: Transaction Signature Verification for Version 0 Witness Program

- Segwit benefits

- Wallet implementation hints

* Brain wallets are wallets where the mnemonic phrase for the wallet is designed to be easy to remember for a user. Examples of particularly weak ones are short and uncreative phrases, like ‘password’ for example.